Many hands make light work. This applies to both the making of the Braamcamp clock, as well as to the restoration of the so-called “Braamcamp” clock, both perfect examples of team work.

On occasion, the Rijksmuseum’s conservation studios collaborate with other museums, in this case Museum Speelklok in Utrecht which,in 2016, acquired this monumental clock with its elaborate musical mechanism and produced by the London clockmaker Charles Clay (who died in 1740). This blog tells the story of the restoration project.

The Braampcamp clock’s oak carcase of the over-life size case is veneered with mahogany (the pedestal) and with ebony (the dome), and is ornamented with gilt bronze decorations and brass mouldings. The arches of the dome frame gilt bronze ajour screens, which are masked behind with red fabric.

The clock dial is located in the front arch and is relatively small with a diameter of no more than 15 cm, and is incorporated into a large copper plate elaborately decorated with reliefs and an oil painting of Apollo and the Muses on Mount Parnassus with Minerva. The painting can be attributed with some certainty to Jacopo Amigoni (c. 1685-1752). The clock face is framed by a gilt bronze, low relief architectural perspective with obelisks surmouned by silver urns flanked by plinths holding silver urns and cast silver high relief figures of Apollo and Diana modelled by John Michael Rysbrack who was also responsible for the lively group of the arts below, also of silver and cast in high relief.

The muscial mechanism consists of an organ which plays a variety of airs by Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759). Händel (from Halle), Amigoni (from Naples) and Rysbrack (from Antwerp) were three of the leading figures in London’s cultural life during the first half of the eighteenth century, and all were involved with the dominating art form of the time, the fashionable Italian opera. As the most popular musician of the day, Händel was the obvious choice for such an extravagant and expensive item as Clay’s clock, and was possible responsible for arranging his melodies for this as well as other clocks by Clay.

The Rysbrack reliefs reappear on a number of Clay’s other musical clocks, while Amigoni was also responsible for painting all four faces of Clay’s most eleborate clock, now in the British Royal Collection. Rysbrack and Amigoni were also involved with the scenography for the London operas, so that Clay’s choice of them to complement Händel’s music is not surprising.

Although the clock’s original owner is unknown, from 1759 until 1771 it belonged to the celebrated artcollector Gerrit Braamcamp (1699- 1771), a Dutch merchant based in Amsterdam. After Braamcamp’s death, it was sold at auction and bought by his family who settled in Portugal where it remained until the 20th century, having passed through various collections including that of the infanta Maria Isabel. By 1972 it was owned by the Parisian collector Robert de Balkany, from whose auction it was acquired by the Museum Speelklok in 2016. While the clock and organ mechanisms have been restored by the expert conservators of Museum Speelklok, the case, pedestal and ornamental elements have been treated in the conservation studios of the Rijksmuseum, which has the necessary expertise not only in the conservation of the woodwork but also the metalwork and oilpainting. Although the clock case seemed at first sight to be in reasonable condition, a closer look revealed some serious problems.

The mahogany veneer was loose and lifting off the wooden substrate in places, and there were numerous lacunae both in the veneer and the mahogany carvings. The solid wood of the panels and the plinth were cracked and the veneer in these zones had split and was blistering with areas of discolouration along the cracks. The gilt bronze, silver and brass decorations were dirty and corroded. Diana’s quiver, a characteristic attribute of the goddess casted in silver, was missing, and the red material behind the open work metal screens in the dome was loose, discoloured and damaged. The surface of the painting was dirty and some small flakes of paint had fallen off.

Although the transparent finish on the pedestal was in fairly good condition, its high gloss and reddish hue were considered disturbing. The reflection of light sources by the glossy finish impeded the experience of the subtle nuances in the structure of the mahogany. The thickness of the finish had made the edges of the carvings less distinct. Inspection with Ultra Violet (UV) light in combination with pyrolysis-gas chromatography/ mass spectrometry (py-GC/MS) analysis revealed that the glossy finish was a shellac that had been applied after the original finish (a mix of terpene resins such as pine, sandarac, shellac and larch) had been removed. In the zones that are more difficult to reach the remains of this resin mixture where still present and fluoresced greenish under UV radiation. Scrape marks on the veneer indicate the terpene resins had been removed mechanically.

The Museum Speelklok wished the case to be restored in such manner that its original appearance could be appreciated and the high quality of materials and craftsmanship be apparent. The high gloss finish on the pedestal was completely removed with solvents. Multiple layers of beeswax were applied. The satin patina of the beeswax, which was commonly used in the first half of the 18th century, allows for the three dimensional effect of the interlocked grain of mahogany to be experienced. Cracks and lacunas in the veneer and solid wood were filled and loose parts were consolidated.

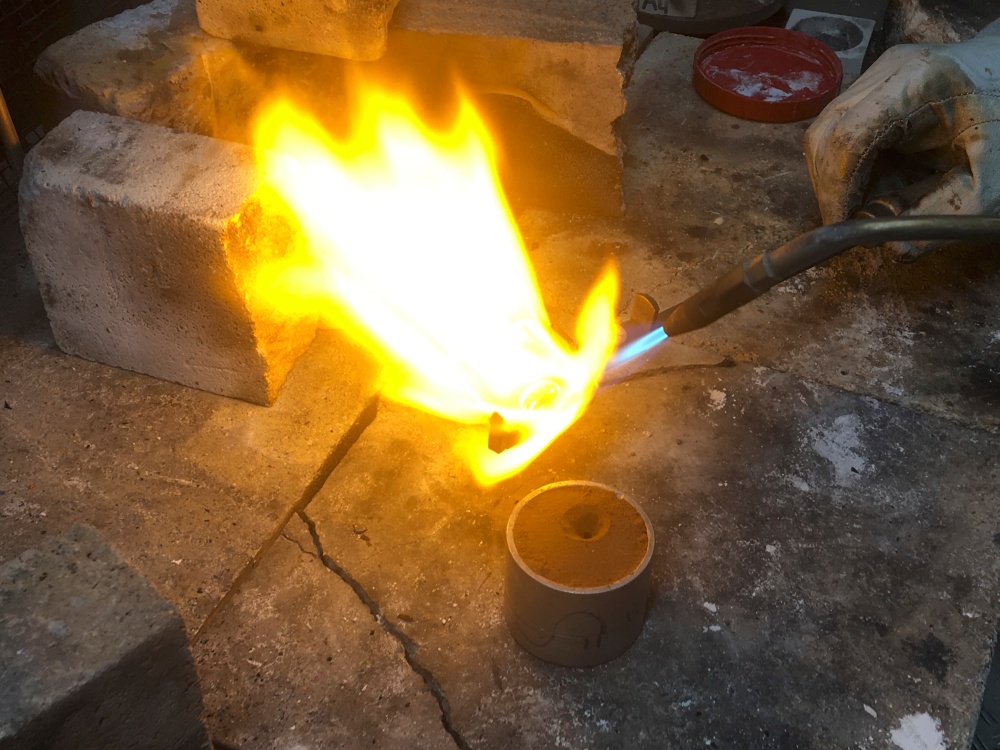

In consultation with the metal conservation studio it was decided to clean the metal decorations and polish them to a soft gloss. The gilt fired brass was cleaned, and a transparent varnish applied to the metals to protect them from future corrosion. A replacement for Diana’s lost quiver was cast in silver using old photographs of the Braamcamp clock.

Analytical research with Infra Red (IR) and UV light was performed on the painted clock face, which was cleaned and the lacunas retouched.

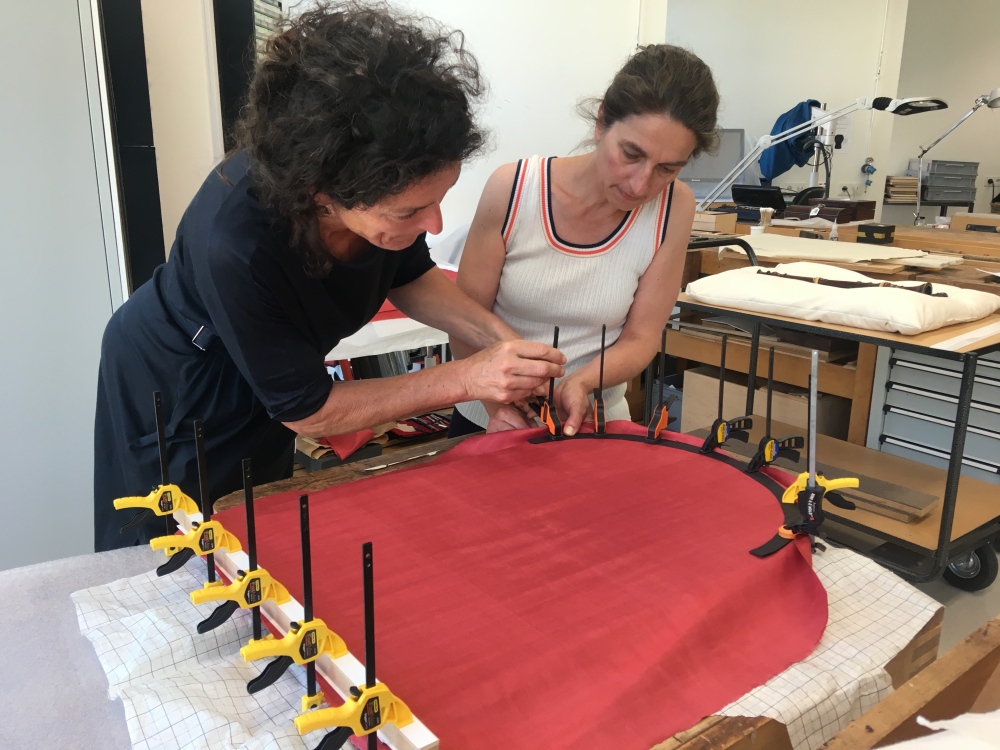

The textile, identified by Rijksmuseum’s textile conservators as a modern synthetic fabric, was removed and replaced by a silk one, dyed in the right shade of red.

During the treatment which took more than six months, the staff of the Museum Speelklok visited the Rijksmuseum’s studio on a regular base in order to follow the progress and discuss the options for treatment.

This was true teamwork: Paul van Duin, head of furniture conservation, who supervised the project. Tirza Mol was invited to perform the conservation treatment. Anja Smets, private textile conservator dyed the silk in the shade of red that was selected by Museum Speelklok’s head of collections Anne-Sophie van Leeuwen. Analytical research with Infra Red (IR) and UV light on the painting was performed by Giulia de Vivo from the paintings conservation department, who also retouched the lacunae in the paint and cleaned the surface of the painted dial face. Metal conservator Arie Pappot and Tirza Mol worked together on the reconstruction of Diana’s silver quiver.

With many thanks to all who worked on this special object and to Tirza Mol and Duncan Bull for the information on the artists, artisans and composer who worked together on this wonderful clock.

Erma

The “Braamcamp” clock is currently on show at the exhibition ‘Als kunst je lief is/For the love of art’ at the Kröller-Müller museum at Otterlo until February 3rd, 2019.